Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Turning a blind eye to convention

Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts presents Thomas Eakins: Photographer (second review)

Thomas Eakins’s pursuit of realism blinded him to social propriety. He sought to convey truth to canvas, to draw from life using live, often nude, models. His approach as a painter and professor ignited controversy, alienated him from colleagues and family, and ultimately cost Eakins (1844-1916) his position at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA).

Long since recognized as among the finest U.S. painters, Eakins’s use of the emerging medium of photography is the subject of PAFA’s Thomas Eakins: Photographer. It is an opportunity to see with 21st–century eyes what caused all the furor 130 years ago.

Putting photographic accuracy on canvas

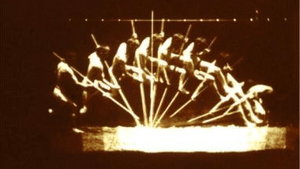

Classically trained, Eakins used photography alongside traditional sketching and life casts to increase accuracy in his painting and, in groundbreaking photographic work with Edward Muybridge at the University of Pennsylvania, to see precisely how bodies moved, creating a cascade of sequential images of models in motion.

Eakins and photography were born in the same era, the daguerreotype debuting in 1839, just five years before the artist’s birth. By the time Eakins purchased a camera in 1880, he was dedicated to replicating life on canvas, not through the gauzy veil of an Impressionist, though he’d studied at the École des Beaux-Arts during the movement’s height, but through the clear lens of a camera. Eakins wanted to know firsthand how the human body looked and functioned from the inside out.

Studying anatomy like a surgeon

He studied anatomy and drawing at PAFA, and sat in on anatomy and dissection courses at Jefferson Medical College. The experience not only produced one of his most celebrated paintings, The Gross Clinic (1875), it foreshadowed an instructional style he would employ at PAFA, where he rose from volunteer instructor in 1876 to director by 1882.

At PAFA, Eakins and a close circle of students made hundreds of figure studies, clothed and unclothed, men and women, in the studio and outside. Settings and surroundings were often immaterial; Eakins was most interested in individual figures, the aspect of a model’s head, how light cascaded over musculature, or how a change in posture altered mood.

Eakins recruited students and family members as models, and posed himself. His wife Susan Macdowell Eakins, a painter, photographer, and former student, was a frequent model. In Susan Macdowell and Crowell children in rowboat at Avondale, Pennsylvania (1883), she poses with his sister Fanny’s children in an idyllic portrait. Macdowell, clothed, sits in the bow of a rowboat pulled in to a creek bank, bookended by two children. A third child stands on a log in the stream. The children are nude, their faces obscured by distance. Later, when nieces Ella and Maggie became PAFA students, Eakins wanted them to pose nude, and Fanny objected strenuously. (Another sister, Caroline, publically denounced Eakins after his dismissal from PAFA.)

The live studies involve adults and children. Even now, even knowing they were intended for the studio rather than for exhibition, some of the photographs are disturbing. Among the photos of adult women, some have cloths tied over their faces, which makes them look like prisoners of war or corpses. And though the studies of children are usually too small and posed so as to preserve anonymity, in one, Boy nude, sitting on draped table in front of printed-fabric backdrop (c1885) the model’s face is clearly identifiable.

Confronting Victorian sensibilities

Eakins taught drawing to women and men using live models and plaster casts made from anatomical dissections. “While some students found his studio environment freeing and experimental,” PAFA gallery notes explain, “others found it distressing and unsettling.”

The photographs on exhibit, principally albumen and platinum gelatin prints, come from a collection compiled by Eakins student Charles Bregler and purchased by PAFA 31 years ago. Many are composed in the Arcadian style of painting, which set people outdoors in peaceful, pastoral settings. Thomas Eakins and students, swimming nude (1883), a study for Eakins’s painting Swimming (1885), does this. It was taken in Lower Merion, which stood in for the sylvan simplicity of Arcadia. Unlike most of the photographs on display, it is carefully composed and offers a crowded frame. Seven people are arranged on or near a large rock, some lounging in the sun, some dipping toes into the water, others, including Eakins, standing waist deep in the lake.

Eakins’s use of nude models was not his only affront to Philadelphia’s genteel society. Models frequently came from the lower classes, a group some considered unfit for association with art students. By the time Eakins removed the loincloth of a male model in front of female students, the hierarchy had had enough: he was dismissed from PAFA in 1886; twenty-eight students withdrew in support.

Looking at everyday life

Aside from figure studies, the exhibition includes photos depicting Eakins’s life as the 19th century was turning into the 20th: A trip to the Dakotas; his father Benjamin testing the new rage, the bicycle; and his closest sister, Margaret, sitting with Eakins’s setter Harry on the front stoop of his home at 1729 Mount Vernon Street, woman and dog wearing similarly bored expressions. There are also portraits of Eakins from age 6 to 65, documentation that was rare in that time.

Eakins taught perspective without recognizing — or perhaps not caring — how his methods looked to Victorian Philadelphia. Whether unaware or willful, Eakins paid a price, at least in his own time, for the blinders he wore.

For Gary Day's review of this show, click here.

What, When, Where

Thomas Eakins: Photographer. Through January 29, 2017 at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 118 N. Broad Street, Philadelphia. (215) 972-7600 or pafa.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.