Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Katharine’s Choice

Steven Spielberg’s ‘The Post’

A compelling human conflict lurks at the core of Steven Spielberg’s newsroom drama, The Post. The only real impediment is Spielberg himself.

As secretary of defense under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson from 1961 to 1968, Robert McNamara dispatched a half-million U.S. soldiers to Vietnam. Of those, 58,000 died before that tragic military misadventure ended in failure in 1975.

In 1965, McNamara privately concluded the war effort was hopeless, even while publicly insisting that “in every respect we’re making progress.” He then commissioned a comprehensive secret study showing how 20 years of government mistakes and deceptions had produced America’s Vietnam quagmire. His purpose, presumably, was to enable his own and future administrations to avoid such disasters without suffering public embarrassment.

Portions of that 47-volume study, later known as the Pentagon Papers, were subsequently copied by one of its contributors, Daniel Ellsberg, and turned over to the New York Times. The Papers' publication in 1971 demonstrated, among other things, that to avoid the humiliation of defeat, the Johnson administration systematically lied not only to the public but also to Congress. They turned an already skeptical public sharply against that war.

The Nixon administration accused the Times of violating the Espionage Act and won a temporary court order blocking the newspaper from publishing more excerpts. It was the first time in history the U.S. government had exercised prior restraint of any publication. That was when the Washington Post, led by its driven executive editor, Ben Bradlee, and its timid and insecure publisher, Katharine Graham, stepped in.

Trump’s Kool-Aid

In this scenario, Bradlee sees publishing the Pentagon Papers and standing up to government as key to his lifelong ambition: establishing his provincial paper as a serious national rival to the hated Times. Meanwhile, Graham, having accidentally inherited a job she was never intended to fill, struggles to prove herself as a chief executive in a business dominated by swaggering alpha males. And, as it happens, the whole drama plays out during the very week the Post’s parent company goes public; an attack by the government might scare off investors and doom the entire stock offering.

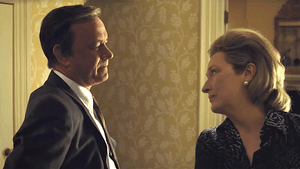

Spielberg’s focus on the coming-out of the Post and Graham (rather than on the Times) is a sound choice. As Graham and Bradlee, Meryl Streep and Tom Hanks make credible human figures with whom we can empathize, even when they're at loggerheads.

The screenplay, by Josh Singer and Elizabeth Hannah, stays largely faithful to Graham’s account in her 1997 memoir, Personal History, with one exception: The script paints McNamara — by 1971 a private citizen and Graham’s friend — as adamantly opposed to publishing the Pentagon Papers. In fact, McNamara encouraged Graham to publish and provided helpful advice about how to frame the paper’s legal defense. And for anyone who has swallowed Donald Trump’s anti-media Kool-Aid, The Post provides a timely, easy-to-swallow antidote about the priceless value of free and independent news media.

Breathless

But to those of us who don’t need such a simple and (to me) obvious reminder, the biggest problem with The Post is its celebrated director.

If you go the movies for dazzling flights of cinematic imagination, Steven Spielberg is your man. Ditto if you want to surrender your brain to a master emotional manipulator. But if you crave intelligence, subtlety, or nuance, look elsewhere.

In The Post, characters rarely converse. Instead, they shout imprecations like, “No shit! This means it’s the goddamn ball game!” Or, "Tell 'em it's from Sheehan — don't walk!" And instead of walking, they rush down hallways and burst through doors, trailed anxiously from behind by the camera, or they race breathlessly up and down stairways and through city streets, dodging taxis.

These characters are cinematic cousins of the congressional aides in Spielberg’s Lincoln, who convey excitement by running all the way from the Capitol to the White House when a horse and buggy would suffice. Or the feverish scientists in Close Encounters who, desperate to locate the spot where a UFO will land, consult not a world atlas but a huge globe, which they dismantle and roll into their hallway.

Moment of decision

Kay Graham’s insecurity is reflected in her constantly dropping papers and bumping into people and things. A Post editor is so frantic to make a call from a payphone that he drops the receiver and scatters his coins onto the sidewalk. As bundles of the latest issue of the Times tumble off a delivery truck into the street, Post editors grab and read them so impatiently that pages blow away in the wind. Such stale cinematic gimmicks are no substitute for the genuine drama that occurs, especially in a story like this, inside people’s heads.

The key question Graham confronts in The Post is: Should we publish the Pentagon Papers in defiance of the government? Bradlee argues, “The only way to protect the right to publish is to publish.” But Fritz Beebe, the Post’s corporate lawyer (Tracy Letts), warns that a government attack could cripple the paper financially. How does Graham resolve this conflict between the paper’s soul and its solvency? With Spielbergian overstatement, as the camera moves in for a closeup, spooky music plays and Graham blurts, “Let’s go — let’s do it — let’s go — let’s go — let’s publish.”

A similar psychological lapse plagued Spielberg’s Schindler’s List (1996), the true story of a German industrialist who, having made a fortune off Jewish slave labor, set up a phony munitions plant to rescue 1,100 Jews. What caused Oskar Schindler’s conversion from exploiter to savior? All we got by way of an answer was a scene in which Schindler, on horseback, witnesses the Jews of Krakow being herded into the ghetto. The camera dwells on his noble equestrian figure long enough to suggest that we are witnessing a transformational moment.

Black’s affirmation

In the best of all worlds, The Post would have been titled Katharine’s Choice, and it would have been made by a more psychologically attuned, female-oriented director.

Still, at the climax of The Post, when I heard Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black’s ringing affirmation (accompanied by suitably stirring music) that, according to the Founding Fathers, “The press was to serve the governed, not the governors,” I couldn’t help feeling that lump in my throat, just as Spielberg intended. Damn, that man knows how to push our buttons.

What, When, Where

The Post. Steven Spielberg directed; screenplay by Josh Singer and Elizabeth Hannah. Philadelphia-area showtimes.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Dan Rottenberg

Dan Rottenberg